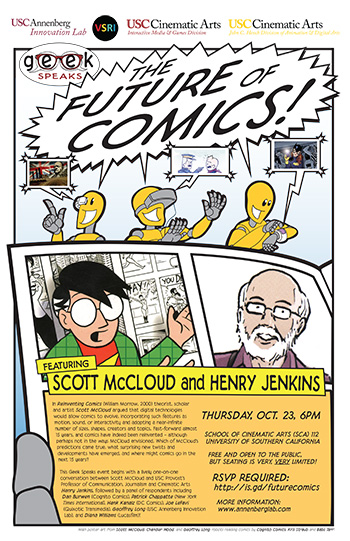

On October 23rd, I had the great pleasure of co-hosting Geek Speaks: The Future of Comics with Henry Jenkins.

I was thrilled to not only reunite Henry with the one and only Scott McCloud for a one-on-one discussion on McCloud’s Reinventing Comics almost 15 years later, but to then get to chair a panel of really brilliant respondents immediately afterwards.

I’ve posted a Flickr album of the event here, and you can find video of the event (although admittedly low-resolution for the time being – we’re still trying to get the high-res versions up) on the Annenberg Innovation Lab’s Vimeo page. Here’s the currently available version of Henry’s conversation with Scott:

Once they were done dazzling the audience, it was my panel’s turn. My panelists included:

- Dan Burwen of Cognito Comics

- Patrick Chappatte of the International New York Times

- Hank Kanalz of DC Comics

- Joe LeFavi of Quixotic Transmedia

- Diana Williams of Lucasfilm and Roller Coaster Entertainment

Here’s the video of our half of the event:

At the heart of much of our conversation was a simple question: “What is the Future of Comics?” I didn’t get to really tuck into some of the more outlandish ideas I’ve got about where comics could be going (especially in virtual reality or augmented reality), so I’d like to republish here an excerpt from the talk I gave last year at the Grand Opening of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at Ohio State. This talk was presented via the gracious hosting of the good Jared Gardner, and was part of a one-two combo I delivered with my fellow transmedia geek and one time high school bandmate (how’s that for a small world?) Tyler Weaver as a setup for Henry Jenkins’ keynote lecture on “Reading the Yellow Kid”.

And now, a flashback to beautiful Columbus, Ohio on November 13, 2013 (I’ve put a Flickr album from that event here, to set the mood), and a jump-cut to the last third of my talk…

A Future of Comics, or, Ten Years of Combining Theory and Practice to Explore Transmedia Storytelling, Affordances, and the New New Comics

…Our projects at the Innovation Lab include exploring the emerging affordances of dynamic e-books, such as Moonbot, William Joyce and Brandon Oldenburg’s The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore or Mirada and Cornelia Funke’s Mirrorworld. Because we’re a Think and Do tank, we’re applying what we’re learning from those works to our own experiments, such as the digital e-book project Flotsam, which mashed up David Wiesner’s beautiful illustrated children’s book with a rich interactive experience that utilized the iPad’s camera, its clock, and its other sensors in fascinating ways.

We’re currently booting up a new initiative at the lab we call the Edison Project, which posits that the media and entertainment industry is at its biggest point of change since Edison invented the Kinetoscope in 1891. The four primary research areas within the Edison Project are the New Creators and Makers, the New Metrics and Measurement, the New Business Models, and the New Screens – where, as the Technical Director and a media inventor style of storytelling geek myself, I’m spending most of my time.

The three big new screens we’re exploring right now are Google Glass, 3D printers, and the Oculus Rift. What’s exciting about these to me is that we don’t know what the affordances of these new screens are yet, and, I’d argue, the best way, or perhaps the most fun way, to discover those affordances is by getting our hands dirty and actually building stuff. Tinkering with Google Glass, 3d printers and the Oculus Rift will help us understand the “new new media” of augmented reality (AR) storytelling, tangible storytelling, and virtual reality (VR) storytelling, and then, for this group’s particular area of interests, perhaps even a “new comics” – AR comics, tangible comics, and VR comics.

AR Comics

Now, we’ve seen AR comics before. Marvel launched its “Marvel AR” initiative at the South by Southwest conference in 2012, and Skip Brittenham and Brian Haberlin’s gargantuan augmented reality-enhanced original graphic novel Anomaly was published in 2012 and was sufficiently well-received, or at least sufficiently conceptually impressive, to be optioned for a feature film by Relativity Media in September of 2013.

These AR experiences share a common mechanic: when a digital camera is pointed at a printed page, a lightly animated 3D model appears as if by magic, superimposed over the page. Google Glass could certainly do something similar – but there are some emerging affordances to wearable AR headsets like Glass that suggest that AR comics could offer quite a bit more.

For starters, Glass relies on a primary UI similar to a kind of “picture in picture” for the real world. The user sees a translucent screen superimposed over the upper right corner of their vision, which the user then swipes through left and right using a touchpad on the frame beside their right eye. Seeing this in action, the temptation to experiment with panel-by-panel comic strips, perhaps with its advancement triggered by a simple blink, is irresistible.

That’s interesting, but let’s go more blue-sky. As the technology advances to overlay more than just one corner of your vision, and as computer vision tech advances for more nuanced recognition of patterns in the real world, it’s possible to imagine a system that composites comic book panels over white spaces in the real world. Sitting in a hotel, an advanced set of AR glasses could overlay panels of a story reshaped dynamically in a way similar to what we did with Ryse, cropping and zooming large panels into dynamic sizes customized for your walls – which will, of course, call into question how “fixed” or dynamic the layout and composition of these images could be to have them still be considered comics.

Either way, what’s funny is that, even if we don’t yet know the full affordances of storytelling with a “new screen” like Google Glass, such explorations of what it means to tell stories, or to make comics, using such new screens helps us to fill in those gaps, to figure out what those affordances of this new medium might be. Again, learning through getting excited and making things.

Tangible Comics

The term “tangible comics” is admittedly idiotic, because traditional paper comics are already tangible. However, in this case we’re inheriting the term from the concept of tangible computing, or, as it’s more popularly known, the “Internet of Things.”

Much of the buzz surrounding this emerging tangible computing space is focused on the 3D printing movement, and rightly so. Early experiments bashing together 3D printing and comics are really interesting – for example, Wizards and Robots from Intel’s resident futurist Brian David Johnson and the Black Eyed Peas’ resident futurist will.i.am includes such transmedia extensions as multiple print artifacts delivered encased in a 3D-printed “crystalline” container.

Perhaps more interesting, at least to me, are the possibilities offered here to update the same “toys + comics” area that I covered in my aforementioned application essay to MIT. This bundling of comics with toys is being currently revisited by Hasbro’s Transformers toys, some of which now include full-sized issues of IDW’s Transformers comics which, much like Mattel and DC’s Masters of the Universe mini-comics from the 1980s, each offer up a story starring its co-packaged action figure.

Where this gets interesting is where we look at the emerging practice of 3D printing really detailed, beautiful custom action figures. As 3D printers continue to increase in their fidelity, and inevitably begin printing in multiple colors with multiple materials and textures, it’s only a matter of time before, instead of toys coming bundled with comics, we’re buying comics that are bundled with exclusive downloadable toys that we’ll print at home.

Again, these are still early days, but tinkering in these directions will begin to help us understand an emergent set of leverage-able affordances for tangible storytelling.

VR Comics

Not a lot of people are experimenting with comics and virtual reality yet – Google “comics AND Oculus Rift” and you get a strip by Scott Johnson about a poor guy joyfully immersed in a VR game while a villain lifts his wallet.

Perhaps this is because, much like “tangible comics”, the idea of VR comics seems antithetical to comics at all. For a clue as to how this might work, consider the approach one Korean company took in developing an app called VR Cinema 3D, which is pretty much exactly what it sounds like – a virtual reality cinema, in which the user can watch regular movies, but without the pesky kids on their dratted cell phones.

That said, simply holding up a virtual comic page in virtual reality is, well, virtually useless. So push it further – what if each panel of a comic could be fully immersive, so the user could choose to step through the frame and wander around each panel in 3D space, so each panel becomes effectively a life-sized, enormous virtual diorama? If that diorama is static and doesn’t use spoken text, but instead employs giant floating 3D text balloons, could they still be recognizable as comics?

Again, it is through such experimentation, such critical making, that we will come to understand what virtual reality will have to offer us as storytellers.

The Next Transmedia Comics

What’s especially interesting here is that this last scenario, as weird as it sounds, isn’t that farfetched. Imagine the next generation of transmedia artists, who don’t want to tell transmedia stories using just comics or games or videos, but also AR, tangible artifacts and VR?

It’s now becoming possible to boot up transmedia mini-production studios. Much like how Adobe’s Photoshop became rapidly repurposed from a photo editing tool into the de facto Swiss army knife of multimedia design, Unity is becoming a de facto Swiss army knife for next-generation transmedia experiences. Art created in programs like Photoshop and Autodesk’s Maya can be imported into Unity, and then exported out into games, videos, virtual reality environments like those used by the Oculus Rift, and even 3D printable toys and artifacts. Within the next 5 years or so, this kind of transmedia production studio may well become the new desktop publishing, and ‘indie’ transmedia stories could become much, much more expansive.

Conclusions and Takeaways

So what’s next? Long story short, right now at the Innovation Lab we’re looking to:

- Explore these new screens

- Discover their new affordances

- Observe what new story experiences emerge

- Prototype, prototype, prototype!

In other words, to get excited and make things! Thank you!